I don’t understand why any civilian would need automatic weapons. Can you tell me why? This past week was a sad, hard mofo of a week, so today I’m telling you three things about my life in guns.

MY LIFE IN GUNS, PART ONE

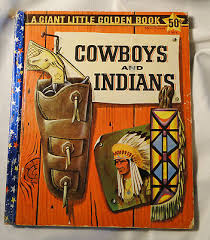

The Giant Little Golden Book titled “Cowboys And Indians” was a childhood favorite of mine. I’d kneel at my bedside with the book splayed open on my pink and yellow quilt, left thumb shoved in my mouth and pore over the pages of illustrations. I was five years old and just beginning to read.

I had no allegiance to either side and the book didn’t sway me. The Indians (circa 1960-something) sported magnificent feathered headdresses that reached far down their backs. Some had face paint, with swaths of color splashed across skin that looked different than mine. The horses they rode–always bareback and with the most minimal bridle and reins fashioned out of rope, were frequently pintos. Some of the pictures showed feathers tied into their manes. Horse-crazy from the outset, I would study the pictures and imagine what it would feel like to gallop bareback across the plains on my pinto pony. I imagined it feeling free and exhilarating.

The Indian’s moccasins caught my eye, too. They were often tall, like boots, with leather fringe that ran down the length of the outside seam. I begged my mother for my very own fringed moccasins and Santa relented and brought me a pair one year. Not the fantastic knee-high ones like the book showed me, but low and tan and made from real suede, with fringe around the ankles. They would have to do.

Most impressive, though, were the bows and arrows. Quivers, either woven from bark or sewn out of animal hide, draped across the Indian’s shoulders and back. The arrows, tipped on one end with feathers, clustered in the quivers, waiting for that fateful moment when the Indian would reach back, usually mid-gallop, grasp an arrow and shoot it across the bow to its intended target.

The lethality of it all escaped my five-year-old brain.

The cowboys were no slouches, either. Rugged men, riding horses that were usually solid brown or black, with regal Western saddles and full bridles with bits and leather reins like I expected. My eyes would fixate on the shiny, silver starburst of the cowboy’s spurs that were buckled onto their boots with leather straps. So ornate, so pretty. It didn’t matter that those shiny starbursts were meant to dig into the horse’s flanks to make them run faster–I just thought they looked cool. And the chaps–oh, the chaps! How I loved the leather chaps the cowboys wore. I had no concept of what purpose they served, but style-wise, I was entranced.

Nothing, though, was more fascinating to me than the guns the cowboys sported. Gun belts and holsters slung low across their hips, the handles of their pistols right there, at the ready.

There’s something about the word “gun” that I’ve always been drawn to. Hard “g”. Short and sweet. I learned to read that word as a five-year-old and I liked the way it looked. I liked the way it sounded and the way it felt, hard, from the back of my throat.

Hard gee. Guh-guh-gun.

My parents got me both a bow and arrow set and my very own holster, studded with silver and complete with a realistic-looking cap gun. I marveled at its beauty and held it in my hand. So sleek and smooth, with what looked like inlaid mother-of-pearl on its handle. I’d pull the trigger and the loud, sharp snap! of the caps felt both startling and satisfying. The puff of gunpowder smoke rose up like incense to my nose.

My siblings and I played cowboys and Indians and I remembered not caring whether I was one or the other. It was play. It was fun. No one died.

It was before we knew better.

MY LIFE IN GUNS, PART TWO

My family and I had taken a lovely day trip to Kopachuck State Park, right outside of Gig Harbor, Washington. It was summertime and I was eight years old. My dad and mom, my brother, Chris, and one of my sisters had spent the afternoon in the park exploring low tide, gathering rocks and shells and picnicking in the woods. It had been an easy day, if somewhat unremarkable. Easy days seemed to be fewer and farther between as I grew older.

The sun was beginning to set, so we piled into our mossy-green Chevrolet van for the hour drive home. Our dad had reconfigured the back seats so that the two bench seats sat facing each other. Chris sat in the backwards-facing seat and fiddled with his BB gun rifle that our parents had bought him after much consternation and debate. He was twelve and adolescence was only making his outbursts and volatility more unpredictable. Mom and Dad always seemed to be grasping at whatever might appease him and bring a little peace to our family.

So they bought him a gun.

I was the baby of the family and a quiet child, but undoubtedly annoying at times to my siblings. Prone to crying and complaining of being picked on by my brothers and sisters. I don’t recall exactly how I was behaving in the van that evening we drove home from Kopachuck State Park, but I do remember my brother shooting me.

It wasn’t accidental. He looked at me, probably told me to “shut up” and shot me with his BB gun rifle as he sat facing me in the van, no more than two feet away. He hit me in the upper right arm and it hurt like hell. Stunned silence at first, followed by my wailing, both from the physical pain of being shot and the shock of my brother actually doing it. My dad pulled the van over and stopped to assess the situation.

I think he took the rifle away from my brother, but I’m not sure. I cried the rest of the way home.

It was nine years later when I overheard Chris telling his friends that he had decided to kill me and my mom once and for all. Our bedrooms were next to each other and I would often hear him and his buddies laughing and getting high and complaining about their lives. This time was different, though. A hush fell over the room when he said it. “Ah, man, no. You can’t really do that,” I heard one of his friends say. Chris continued, telling them of his plan to get a gun and shoot us dead. Just me and my mom. The rest of my siblings had moved out of the house by then and his relationship with our dad was a little less fraught with tension.

My blood turned to ice and I began shaking uncontrollably.

It wasn’t a stretch to imagine him actually doing it. After all, he had shot me once already, albeit with a BB gun. The year before, when I was sixteen, Chris had flown into a rage and attacked my mom and me, hurling a coffee cup at my face, resulting in significant cuts and burns and blood and stitches. He was a living, breathing, ticking time bomb and fear was a constant companion of mine.

That night I told my parents what I had overheard. I spent the night in my old bedroom, right next to my parent’s and further away from Chris’ room. My mom had since turned it into her office and had a small black and white television on the desk. Saturday Night Live was on and I watched it, hoping to take my mind off reality for a bit. A skit with John Belushi was featured, the audience howling with laughter and then bang! Belushi’s character gets shot dead with a gun. The audience clapped and cheered. Fade to black.

When I was a child, I never closed my eyes when I went to bed. Instead, I’d lay awake and simply wait for sleep to take over. Nightmares were a regular visitor.

I turned off the TV and curled up on the small sofa in my old bedroom, eyes wide open, exhausted from emotion but too afraid for sleep.

Two days later, my mom and I moved out of the house I had spent my entire childhood in. I never went back.

MY LIFE IN GUNS, PART THREE

“Someone I loved once gave me a box full of darkness. It took me years to understand that this too, was a gift.” ~ Mary Oliver

Tim was six-foot-four and the only boyfriend I ever had who made me feel small when he wrapped me in his bear hugs.

He was my first love, my first real boyfriend, the first boy to ever tell me he loved me and I, him.

We met while I was at TV school and he was studying to be a dental technician. It was heady and passionate, as all first loves tend to be. His family loved me from the get-go and I felt as though I had immediately inherited several extra brothers and sisters. They were different from my family–loud and boisterous, with lots of drinking on holidays. His father, a prominent dentist in the area, was a mean drunk and would openly berate Tim after a few too many Scotch and waters. “Why are you such a pussy?” his dad would bellow. “Why can’t you be more like your brothers?”

Tim and his father and brothers were avid hunters and fishermen. I grew to expect that Tim would be away on extended hunting weekends each fall. I chided him about killing “Bambi” but learned to accept this hobby of his and even gamely ate a few elk burgers along the way. Rifles and guns were a casual part of his (and now my) environment. I told Tim about my experience with my brother and he pulled me to his chest and held me, promising to always be my protector.

We navigated our relationship with all its inherent peaks and valleys. We were young and inexperienced and both of us prone to intense jealousies. I had unearthed his collection of Playboy magazines one afternoon and confronted him about it. We were driving in his baby blue Ford Pinto and Tim slammed on the brakes in angry exasperation. My body lunged into the seat belt, my tears now hot and salty and out of control. I was deep into my anorexia, my body–bony and thin and my breasts non-existent. I couldn’t comprehend how he could look at those images and still find me desirable. Rather than consoling, Tim sneered and taunted and dared me to get out and leave him, right then and there.

I wiped my face and looked out the window and stayed.

A year later, Tim had moved out of his family’s home and into his own apartment in Tacoma. He seemed better, more even-keeled, with some distance between he and his dad.

New Years Eve arrived that year with a forecast of bitter cold. The rain that had fallen earlier in the week was now predicted to harden into treacherous ice on the roads by nightfall. I hated driving in the snow and ice, so Tim picked me up in his Pinto from the condo I was living in with my mom. We would make pizza together for him to eat and we’d drink to welcome in the New Year, tucked safely in Tim’s apartment. He’d drive me home in the morning.

Dick Clark’s New Years Rockin’ Eve was on so we settled in to watch the ball drop from Times Square. Rick Springfield was performing, singing his hit, “Jessie’s Girl”. I wasn’t a fan of Springfield or pop music in general, so I rolled my eyes and made some off-handed comment about “well, at least he’s good looking.” Tim was already halfway through a fifth of Seagram’s Whiskey and my comment didn’t sit well with him.

“Oh really? Maybe you should just leave now and find little Ricky and finally get the rock star you’ve always dreamed of.” There was an unfamiliar edge to his voice that made my stomach churn.

Tim knew about my teenage years hanging around rock and roll bands, both local and larger. He knew of my weakness for drummers and bass players and my penchant for disappearing into the thrum of a loud, dark concert. But that was then. I was head over heels in love with Tim. I reminded him of that.

He drank more, now straight from the bottle. Something had shifted in him, a darkness encroached and he became scary. He raged on about what a slut I was, how he knew I wanted to fuck every band member in the world and how he could never be enough in my eyes. I pleaded with him to stop. I told him he was drunk and being ridiculous. I told him I loved him. He left to rummage around in his bedroom closet and emerged, holding his hunting rifle. My body stiffened and my heart dropped. I felt the familiar ice in my veins and I shook.

It was midnight now. Tim opened the front door of his apartment in the densely populated complex and fired his rifle off into the clear, black sky. Round after round. Each blast making my shoulders jump to my ears. I ran back into the bedroom, closed the door and sat on the bed, hugging my knees to my chin, rocking to control the trembles. I thought of my mom and how sad she would be if he killed me. I thought of how ironic life was and how guns seemed to follow me.

I was worried that Tim might shoot me, but I was more worried that he’d kill himself. After all, he’d said many times, “One day I’ll shoot myself and everyone will be happy.” It wasn’t a stretch to imagine it happening. He finished off the entire fifth of whiskey, his large frame and family history of alcoholism enabling him to hold a huge amount of liquor.

Eventually he ran out of rounds and whiskey. He opened the door to the bedroom and flopped down beside me. I didn’t move. I sat there as Tim passed out cold on the bed but waited and watched until his breath slowed to a regular, deep rhythm of sleep. I slid down under the comforter and rolled to the far side of the bed, eyes wide open until they weren’t.

I knew it was over then. I’d like to tell you I woke up in the morning and announced that I was breaking up with him and that was that. But I didn’t know how to break up with someone who meant so much to me, someone I loved but who I knew was so, so wrong for me. We had survived that night, but the wounds were deep.

Months later, Tim broke up with me, telling me he had found someone at work who he was interested in dating. I was appropriately devastated for a week or two, until my best friend picked me up, brushed me off and showed me how much more living I had to do.

Tim and I stayed in casual contact over the next few years. The girl from work broke up with him. He asked me to come back, but it was too late. He showed up drunk one night to a club in Pioneer Square where my friends and I were watching one of our favorite bands. Over the clatter and din of the crowd and the band, Tim asked me to marry him. I laughed and told him he was crazy. He said something shaming about the length of my miniskirt. He stumbled out on to the sidewalk, alone.

Five years later, I called Tim to tell him I was getting married. I wanted him to hear it from me, rather than through the gossip of the grapevine. He took it pretty well and asked who it was. I told him it was a boy from a band I had met and followed. “Congratulations,” he said sarcastically, “you finally got your rock star.” I wished him well and hung up.

That was the last time I spoke with Tim. A few years ago, I found him on Facebook. Living in Dryden, just east of the mountains. His timeline, mostly a collection of Ted Nugent gun memes and greetings from what seemed to be young nieces and nephews. No mention of marriages or relationships or children of his own. His profile picture depicted what looked like a mountain man. Full, bushy beard. Long, scraggly hair.

I recognized his eyes.

I didn’t reach out to him or send him a friend request. I was still afraid. Worried that he might want to meet in person or try to find me. I just wanted to know he was okay.

Not long ago, I typed his name into the Google search bar, followed by the word “obituary.” I don’t know why. I just did. The first hit popped up with a link to a funeral home’s memorial page. Tim had passed away just a few weeks prior, right after the long Labor Day weekend. Right before hunting season.

There was no formal obituary or service planned, no condolences or virtual candles lit on the funeral home’s page. No mention of how he died. Nothing. No one.

I told myself maybe he had succumbed to cancer. Perhaps a car accident. But the same voice that had told me to type in the word “obituary” also told me it was most likely something else.

It wasn’t a stretch to imagine him actually shooting himself.

Tim was my box of darkness. It’s taken me years to understand that he, too, was a gift.