Fear.

I don’t consider myself an anxious person by nature, but I’m well aware of the fears I have.

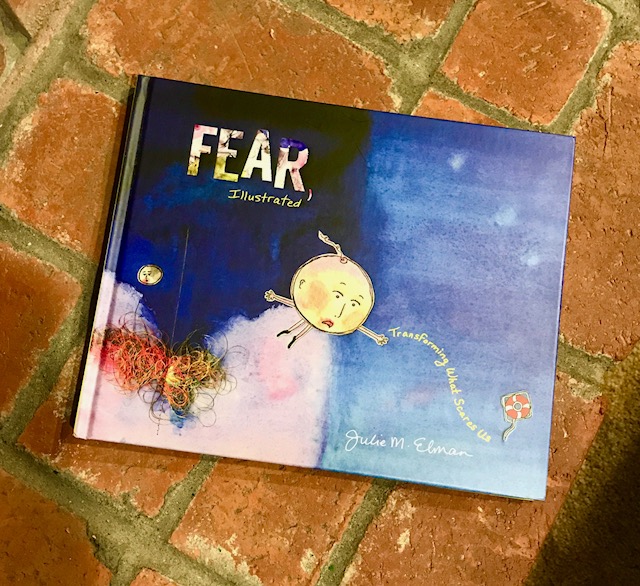

It was Christmas morning when I unwrapped this book--Fear, Illustrated, by Julie M. Elman. Sent to me by my brother in Athens, Ohio, it was as if it had been written for me. As I thumbed through the book and its fantastic illustrations, I saw my quirky self reflected back from its pages. We all have fears, some more than others. And while I’ve often been teased for the strange fears I have, I don’t think I’d necessarily trust a human being who claims to have no fear of anything.

Just for perspective, here is a partial list of things I am not afraid of: going to the dentist, public speaking, big cities, needles, raucous punk clubs, parallel parking, growing older, confrontation, sushi and horses.

Now, I’ll tell you about one fear I’ll always have, another fear I’m working on, and one final fear that I’ve had to face and live through.

SNAKES

The backyard of the house where I grew up seemed big and expansive, as all things seem to feel when you’re a child. We had a large deck that wrapped around and led to a patio, which then led to the lawn, which was terraced into two parts. The upper lawn–where most of the action happened–and then a gently sloping grade which took you to the lower level where wild Oregon grape shrubs and my parent’s failed goldfish ponds were tucked. My siblings and I would take our little green army men and cowboys and Indians and recreate epic battles amongst the bramble and broken concrete.

My father liked to spend hot summer afternoons working in the yard, wearing nothing but his tiny red Speedo briefs. His psoriasis was severe and extensive, covering nearly all of his body except for his face with an angry, scaly, red rash. Clothing would often rub and irritate his skin even more, so he took advantage of the few summer days warm enough to expose as much skin as possible to the sunlight. Although a common sight for me, I was mortified when friends would come over and witness this. They’d stop in their tracks and take in the sight of my father, hairy chest, belly out, scaly chicken legs and softly mutter “oh” as I quickly ushered them into my bedroom to play.

When I was old enough, I mowed the lawn. First, with a rotary push-mower, which took forever and whose blades would jam if the grass was too long. Later, my dad proudly bought an electric model–complete with a long, snaking cord that needed to be plugged into an outlet at the house in order to run. The cord was cumbersome, always getting in the way and I constantly feared it becoming caught in the mower blades and me being electrocuted to death.

But the threat of electrocution was nothing compared to my fear of snakes.

After mowing the main level of lawn, I’d park the mower at the top of the hill, run inside for a cool drink and an bushel of courage. You see, the snakes lived down there. On that lower level, they found refuge in the terracing stones and would slither out on the warmest afternoons to sun their scaly skin, much like my father liked to do. Early in the season, I was safe and could successfully mow both sections of lawn without incident. But come August, all bets were off. Always wanting to do a good job and be praised for my efforts, I’d steel myself and start the mower up. Things would be going smoothly, confidence increasing, so very sure I was in the clear.

And then it would happen. It always happened.

As if laying in wait, the snake would appear, sometimes just one, but on the worst days–two. I’d often hear it first–the subtle rustle of the grass, the slight slither of movement. There was no thought, just instinct and adrenaline. A blood-curdling scream and a swift sprint to shelter in my house, abandoning the mower and its ridiculous cord down below. It would usually take a day or two before my father or a braver, older sibling would finally finish the job and bring the mower back to the snake-free confines of the garden shed.

It’s just a harmless garter snake! everyone tells me. There is no such thing, I reply.

My family was camping in southern Oregon, on our way to the Shakespearean festival in Ashland when my sister and I awoke early, before the rest. Let’s go for a hike, my sister suggested, so we set off towards the rocky hillside that towered at one end of the campground. Clambering up the boulders, I was all of nine years old and thrilled to be included in this adventure. Higher and higher we climbed until I turned, hearing an ominous rustle. There, just beneath the cover of a large boulder, lay a coiled rattlesnake, diamonds on its back, shaking its tail. No thought, pure instinct and adrenaline, blood-curdling scream, one sneaker lost in my desperate scramble back down to the campground, sobbing hysterically.

I woke up the entire campground that morning in southern Oregon. I like to think I warned everyone about the dangers of rattlesnakes nearby.

Even today, I will double-back and retreat if I see or hear a snake on the trails in the woods by my house. I cannot look at a photo, let alone a video, of a snake. And don’t even suggest exposure therapy to me.

Snakes and I will never find peace.

BRIDGES

I spent the first two decades of my life in a place called Lakewood. Unlike some places whose names are descriptive but not at all indicative of the actual environment, Lakewood really has five lakes and a whole lot of woods. It’s changed massively over the years, but back then, Lakewood was an idyllic place to live and play.

The second largest lake in Lakewood, and the one I lived nearest to, is Lake Steilacoom. From our back deck we had a peek-a-boo view of the lake, our house just one lot away from the water. I’d often ride my bike down the narrow and winding Interlakken Drive, past stately stone mansions and more modest Colonials to get to my friend’s house on the other side. A bridge spanned the width of the lake, sometimes filled with optimistic fishermen or mischievous teens. Once on the bridge, I’d pedal my bike as fast as I could, looking straight ahead, legs tingling with nerves and let out a big exhale as I got to the other side. As summer neared and school emptied out, I heard tales of older teenagers tossing others off the bridge–a rite of passage, a ritual of sorts. Not any kind of swimmer myself, I consciously avoided the bridge during most of each June.

Bridges freak me out.

It didn’t help that not far from me was the Tacoma Narrows Bridge–also known as “Galloping Gertie”. The black and white footage right before its collapse in 1940, its bridge deck undulating like a belly dancer’s midriff, is permanently etched in my brain. We’d often take the Narrows Bridge on our way to Gig Harbor and points west for a day trip or camping. I’d hold my breath, not daring to look left or right, until we safely made it to the other side.

As I got older, I tried to figure out what it was about bridges that frightened me. The floating bridges across Lake Washington in Seattle don’t bother me much, even when the wind blows the water up and over my car. If I can see the looming expanse of the bridge in the distance before I cross it, my anxiety level increases substantially. The Astoria-Megler Bridge, which connects Washington and Oregon at the mouth of the Columbia River is a classic example. Even simply driving past this bridge on my way to the Oregon coast shoots shivers down my spine. Pitch and grade seem to make an difference, too, none more anxiety-inducing than the Eshima Ohashi Bridge in Japan. I have nightmares about that bridge.

And like most fears, it’s not rational. I know the bridge won’t break. I’m fairly certain I’ll be fine. And yet.

It wasn’t long ago that I was New York City with my kids. Taking a walk across the Brooklyn Bridge was on our bucket list of things to do while we were there. Our Airbnb apartment sat on the Lower East Side, not too far from the Brooklyn Bridge, but much closer to the Manhattan Bridge. It was Friday night and we had spent the day traversing Central Park and browsing at the Met. My feet were blistered and I had just come back from a much-needed foot massage in nearby Chinatown. The three of us, exhausted and sore, but we were in New York City on a Friday night.

“Hey, let’s walk across the bridge!” my son suggested with the energy of someone thirty years younger than me.

We decided on the Manhattan Bridge–a short ten-minute walk from our apartment. The sun had already set on a warm summer night, the city aglow with shimmering lights and bustling energy. My feet, still greasy from my massage, slipped and slid in my flip-flops, reminding me of my blisters. But we were New York City on a Friday night!

As we neared the bridge entrance, my breath quickened. I felt the familiar trepidation creeping in. My kids knew about my phobia and checked in regularly. How you doin’ mom? they’d ask. I’m okay, I assured them, trying to convince myself.

There was a broad, separate path for pedestrians and cyclists on the bridge, so the rush of traffic didn’t affect us much. Steadfast in my goal, I trudged on as the bridge deck rose from the surface street, approaching, but not yet above the East River. I can do this I can do this I can do this ran the mantra in my head. I wanted to be brave for my kids. I didn’t want to be the scaredy-cat mom. I wanted to share this victory with the people I loved the most. I imagined the high-fives and atta-girls I’d collect across the river in Brooklyn. How proud they’d be! How proud I’d be! And then I remembered I’d have to cross the bridge once again, all the way back into Manhattan.

The bridge rose higher and the East River was now becoming visible not too far in the distance. I took deep, slow breaths, but vertigo set in and my head began to spin. My legs, buzzing with that familiar tingle. I don’t think I can do it, I told my kids. They cajoled, they encouraged, they offered moral support. I didn’t want to ruin the experience for them with a full-on panic attack, so I decided to turn back and let my son and daughter continue on to Brooklyn and back on their own.

Alone and only a little bit disappointed–after all, I was still in New York City on a Friday night–I made my way back down to the bridge entrance. Finally on my own, I was able to slow down and immerse myself in all the sights and sounds and smells of the city–taxis and cyclists, all in a focused rush to get somewhere important. I breathed in the perfume of wood-fired pizza from a sidewalk bistro mingling with aromas of garlic/ginger/soy/seafood as I neared Chinatown. I stopped at a Thai ice cream shop, ordered a cup of matcha rolled ice cream and took it back to our apartment. I sat on the balcony, three stories above the bustle, and waited for my kids to return. I decided to give myself grace rather than wallow in defeat.

There’s something heady about facing a fear and giving yourself a personal challenge. It’s powerful stuff, even if you don’t succeed. I know I’ll make it back to New York City one day soon. In my mind’s eye, I imagine myself confidently striding across both the Brooklyn and the Manhattan bridge by myself. Maybe I’ll document it with a video on my phone. Maybe it will be a private victory. Maybe I’ll bring someone with me for moral support.

No matter how I do it, I like to finish what I start.

MY PARENTS DYING

Spoiler alert: my parents died.

I was the youngest child of seven kids. My mother was forty-five years old when I was born. Even by today’s standards she would be considered an “older mom”, but back then, it was virtually unheard of for a woman of her age to give birth. I’ll be fifty years old when you’re in kindergarten! my mom would often lament.

I was always aware that my parents were the oldest parents on the block. The oldest parents at my school. The oldest parents of anyone I knew. I’m not sure how or when it began, but I was always aware of death and afraid that my parents would die.

Mortality on my mind.

As a very young girl, I’d lay in bed at night, reciting the familiar prayer, “Now I lay me down to sleep…” silently to myself. At the end of the verses, I’d add “And please let my mom and dad live for many, many, many, many, many more years.” I’d often drift off to sleep in the midst of the “manys” and wake up, worried that I had jinxed it somehow.

My father was a heavy smoker and developed heart issues as he aged. After a scary episode while he was teaching at the college, my mother returned home from visiting him in the hospital. “I just didn’t think I’d lose him this soon!” she sobbed, still frantic from the incident. Her distress distressed me, but I also felt secretly pleased that she seemed to still care about him. My parents had a complicated and imperfect marriage. As it turned out, my dad made it through the crisis. With a new prescription for nitroglycerin and a diuretic, life returned to normal.

Through my childhood and teenage years, my mom had a few serious heath scares and we all lived under the threat of my unpredictable, sometimes violent brother in the house. But no one died.

I consciously counted the milestones in my life my parents were around for: establishing my career, getting engaged, getting married, buying a house, having my first child. When my son was two, my dad became critically ill.

Other than my grandparents, with whom I wasn’t especially close, I had never lost someone I loved. This was it, I thought. Here we go. I had to prepare. I threw myself into research, buying books on death and dying, reading about grief and what it felt like, trying to imagine life without my dad. He was always stubborn and a bit cocky and wasn’t ready to die. He talked about wanting to live to see the year 2000.

But he did die.

The hospice nurse called me the morning of his death. Your father is showing signs of dying soon, she told me. I asked her to be specific. Tell me what you mean, I insisted. Calmly, compassionately, she listed all the physical changes he was going through until I was satisfied. You should come now, she said.

My father died before I got there. I’m pretty sure that’s how he wanted it. Or at least that’s what I’ve told myself.

I had never seen a dead person before but I wanted to see my dad. I entered his room and saw a man’s body in a hospital bed, eyes closed, mouth slightly ajar. That’s not my dad, I thought.

My dad had left the building.

It was the middle of March when my father died. Corned beef and cabbage were simmering in the oven that evening, the Mister and my son playing quietly downstairs. I stood at my bedroom window upstairs and gazed out at the blustery day, letting my grief wash over me in unfamiliar waves. My eyes hurt from crying. So this is what it feels like to lose my dad, I thought. I couldn’t believe that everywhere else, life just went on, as if nothing had changed. Because everything had changed. I turned to leave when out the corner of my eye I caught a flash of color rise up in the gray sky. A bright red mylar balloon, set free from somewhere, swirling and whirling in the wind, floating up into the clouds. I squinted as I made out the words on the balloon:

I love you.

Me, too, Dad. Me too.